THE last three hours of the earthly Life of our Lord were the most solemn of any that He spent in this world before His Death. The active agents in His Passion retired, as the darkness drew on, and there was at last great quiet and calm silence around the Cross. The earliest of the Seven Words may have been spoken soon after the Crucifixion had been accomplished. Indeed the Evangelist seems almost to speak of the First Word as if it had been uttered while the process of the Crucifixion was going on. " Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do,"1 or what they are doing. We must allow some space of time after the Cross had been fixed in its socket, for the outburst of the mockeries and jeers from the Chief Priests and the crowd and the passers by, as also for the division of the garments and the fulfilment of the prophecies thereby. But St. Luke puts the first Word before the division of the garments. The second Word, also, may have come early, for the reproaches of the impenitent thief seem to have been suggested by the mocking's of the crowd. It is also probable that the title was fixed on the Cross after our Lord had been fastened to it, and the Chief Priests must have had some time to read it and to make their complaint to Pilate concerning it. These things, therefore, may have taken place while the darkness was growing deeper and deeper, and then there may have been silence, broken only by the words which passed between the soldiers as they watched our Lord, until the time came for the third Word.

We are not now attempting a complete commentary on the incidents of the Passion, and we must pass on rapidly, even from the consideration of these wonderful sayings of our Lord on the Cross. Every Word of the Saviour of the world on His throne of suffering must be considered as fraught with meanings of immense depth and sacramental import. This is a general principle in the interpretation of these words. We must confine ourselves to those aspects of the whole which concern more immediately our Blessed Lady. Every thing, indeed, that happened must have concerned her in the fulfilment of the office of which we have so often spoken, of following as closely as possible the thoughts and affections, as well as the actions and sufferings, of her Divine Son, and in this respect all the incidents on Calvary must have struck her most deeply. She must have been the first to note the fulfilment of the prophecies with regard to the raiment which was divided, and the seamless robe for which lots were cast, that it might not be torn. It must have pained her deeply to see these relics of our Lord touched by hands so unworthy of them, and in the possession of persons so ignorant of their priceless value and sacred character. But at the same time the exact carrying out of the words of the prophecy was to her a subject of the tenderest thanksgiving.

The title was another subject of contemplation for her. It was in one way the fulfilment of the promise first made to her by St.Gabriel at the Annunciation, that the Lord God would give unto her Son the throne of His father David. She had noted all through the manner in which His royal dignity was perpetually brought forward in the arrangements of Providence. Through the taunts and jests of the unworthy priests and the rude people she could see the Divine decrees which were securing the salvation of the world by the very apparent helplessness and weakness of Him Who was asked to come down from the Cross and receive their faith and allegiance, Who was said to have saved others but not to be able to save Himself, while if He had chosen to save Himself, as they said, they would have been left without any chance of salvation. Her prayers would rise for all, but most perhaps for the priests and for the poor thieves crucified by His side, blessed indeed in such a favour if they could but learn to understand their privilege. The contemplatives attribute the conversion of the one to the prayers of Mary. And certain it is that she, who was always so full of charity and so much on the look out for subjects for her intercessions, must have prayed especially for those in such a position as this.

As the silence came on with the increasing dark ness, it is natural to think that our Blessed Lady must have set herself to ponder most deeply the Words which fell from our Lord's lips one after the other.. The two first Words, which have been already mentioned, were full of the most Divine charity and of the largest munificence and bountifulness. Our Lord said nothing by way of complaint, He uttered no expression of pain. His thought was first for the spiritual and moral miseries of the poor men who were or had been engaged in fastening Him to the Cross, and in otherwise insulting Him and putting Him to unnecessary torture. It was for these that He first broke silence, "Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do." There was this excuse to be made for them, although with regard to many of those concerned in His Passion the words could not apply so fully as to others. The Chief Priests had had many and great opportunities of knowing what they were doing when they contrived His Death, and He Himself had said of them that they had both seen and hated both Himself and His Father. 2 Still there were things about the Passion as to which they certainly did not understand what they were doing, and His loving Heart fastens on these and makes them the ground of His pleading for them to the Father, Whose wrath they were provoking to the uttermost. He uses the loving word Father, which He had not often used in the course of the Passion, because He was at that time Himself under the wrath of the Father for the sins which He had taken on Himself to expiate. But He speaks now as with power and right, as having it as His privilege to plead for those to whom He might wish the merits and fruits of His Passion to be applied, and thus it is an expression of a wish, and not simply a prayer in which He begs the boon for His enemies on the ground of their ignorance.

This Word must have presented to the mind of the Blessed Mother at the foot of the Cross a large measure indeed of mercy. For there is no limit in the petition, and as far as its words are concerned, they embrace the whole multitude of those who have had any share in the bringing Him there. The limit can only be found where there is no ignorance that can shield them, or, what is far more dangerous, where there is in themselves that determined obstinacy of heart which will not open the door to the grace when it knocks thereat. But in the intention of our Lord and in the mercy of the Father which this petition was to set in motion, there is absolutely no limit, and thus within the range of this mercy might have been found the High Priests themselves, or the traitor Judas, if he had not already placed himself beyond the reach of mercy, there might have been found the false witnesses, and the soldiers who had scourged Him savagely and mocked Him in the Praetorium, and the fickle people who had called for the liberation of Barabbas, and who cried out. " Away with Him ! Crucify Him ! " Thus our Lord's first speech on the Cross would open to our Lady the boundless treasures of His loving mercy, at the time when He might have been expected to speak rather in judgment or in remonstrance, for the very great and fresh provocation which their treatment of Him on the Sorrowful Way might naturally call for. What might He not have in His Heart to give to His friends, if He had so large a measure of bounty for His enemies ? And the words may perhaps be understood as implying that it might be made a kind of merit in these enemies that, without knowing it, they were bringing about the execution of the Divine decrees, which involved so much of endless glory to the Father, of honour to our Lord, and of good to mankind. Unwittingly they were contributing to the accomplishment of the great design of wisdom and mercy, and so it might be a part of His royal bountifulness to let them have their share in the fruits of that counsel.

The words of the thief on the cross may, as has been said, have been primarily suggested by the reviling's and jeers of the scribes and priests who stood and mocked at the sufferings of our Lord. For such insults and barbarities have a natural way of propagating themselves, of being caught up by one person after another, and so when the passers by joined the priests, and the soldiers also took part in the reviling, the poor suffering thieves by His side may have been tempted to take their part also in the insults. One at least did so, and we are not obliged, by the words of the Evangelists, to think it certain that the other joined him. Mary was there at the foot of the Cross, praying, as was her wont, for those before her who were in the greatest need, and no one could be in greater need than these fellow-sufferers of our Lord, because their time could not be long, their blessed opportunity would soon pass away. Was there to be no victory of grace at this solemn time ? Was our Lord really to pass away on the Cross, with no voice lifted in His defence and in confession of His innocence and of His dignity ? Surely if this had been so, the stones would have cried out. And so from the very cross by His side, amid the deepening gloom of the advancing darkness, there came forth that clear faint voice, first rebuking with great charity the other sufferer, "Dost thou not fear God, seeing thou art in the same condemnation ? And we indeed justly, for we receive the due reward of our deeds, but this Man hath done no evil." And then the charity and faith of this rebuke swelled up still higher, to the level of a great act of hope and a great and full confession of the truth which was being trampled under foot by the whole world, to a loving and confident prayer, not for any specified boon of pardon or of deliverance, but simply that our Lord when He came into His Kingdom, would remember the little service that had been done to His honour. "Lord, remember me, when Thou shalt come into Thy Kingdom !"

If St. John, or our Lady herself, or one of the disciples, had raised a voice in defence of our Lord on this occasion, it might have been said that they were His friends and bound to speak for Him, and their witness would not have been so precious to the Sacred Heart nor so efficacious in the eyes of the world as this witness of the dying thief. Even criminals are listened to with respect hen they speak from their place of punishment, and with the dews of death gathering on their brow, and this man, as far as he spoke for himself and for his companion, spoke nothing that could not be acknowledged by all who heard him as true. It was different when he turned to our Lord and made his wonderful confession, for in that was included a perfect Christian faith in our Lord as God and as King, in the certain advent of His Kingdom, and of His power to reward any service rendered to Him. This confession was made at the time when He was hanging on the Cross, and when His enemies were jeering at His apparent want of power to help or to save Himself. Moreover, the petition is made in the humblest and most modest way, not as if he had done any great service or might claim any striking reward. He only asks our Lord to re member him, and the request implies that the mere thought of him by our Lord was enough, and was certain to carry with it an abundance of relief and recompense. The consolation which this humble prayer and confession would have furnished to the heart of our Lady must have been boundless, and it must have conveyed also the assurance that the grace of the Crucifixion was already at work, that our Lord had begun to exercise, from the wood of the Cross, His royal and sovereign authority.

But there was still more occasion for wonderment and for rejoicing, when the answer from our Lord to the petition of the thief revealed once more the magnificence and lavish liberality of His giving, now that He was thus lifted up on His throne. The thief had asked merely that our Lord would remember him. It is one of the arts of prayer, which the servants of God learn by practice, in dealing with God in this way, not to dictate to Him, as it were, not to point out precisely what we think best, but to trust to His wisdom, in choosing His own boon, as well as to His liberality in giving us any boon. When our Lady brought about the first great miracle, she only said, "They have no wine." When the sisters of Lazarus desired our Lord's help for their brother, they only said, "He whom Thou lovest is sick." So now the thief, as if he were well acquainted with our Lord's ways, only says, " Lord, remember me." Thus the reward for his confession was to be measured rather by the bountiful instincts of the Sacred Heart than by the feeble hopes or merits of the humble petitioner by His side.

Dismas had said, " Remember me, Lord, when Thou comest into Thy Kingdom," speaking of a time which to his mind was probably in the distant future, content to wait till then, in the hope that then at least some kind of deliverance might come. But the Sacred Heart could brook of no delay, and the boon was not to be a mere remembrance, but the highest boon that could then be given, the boon that was to be given in a few short hours to the most exalted of His saints in the next world. " Amen, I say to thee, this day thou shalt be with Me in Paradise." For what more could be said of Joseph or John Baptist, or the most favoured of the ancient saints, than that that day they should be with our Lord in Paradise ? For where our Lord was, there would be Paradise, although as yet Heaven could not be opened, nor the general resurrection anticipated. This poor sufferer, who had hung for a short space of time on the cross by the side of the Son of God, who had just made his short but perfect confession, exercised the duty of charity to his brother thief, and declared before Heaven and earth his faith in the innocence of our Lord, in His royal dignity and in the Divinity of His Person, was to receive no less a gift than this of sharing immediately in the bliss of Paradise, by the side of Him. The merit of his confession, together with his patient suffering, was to cancel at once the guilt of all his sins and all the pain due to them, it was to deliver him from any detention in Purgatory, it was to make him pass at once from the cross as soon as he had breathed his last to the abode of the blessed now made into Paradise by the presence of our Lord. But far above all, it was to make him our Lord's companion in glory, as he had been in suffering and shame. "Thou shalt be with Me!" that was the essence of the blessing. If such was the reward of a single confession under such circumstances, what might not be expected from a liberality magnificent for those who had suffered long and patiently for our Lord ?

In truth there may, perhaps, be a certain intentional advance in the three first Words from the Cross, which may help us to understand them better. It is something more to have the promise of Paradise immediately, than to have the prayer made to the Father that the sin of participation in the Crucifixion may be forgiven, on the allegation of their ignorance. That was a splendid boon from our Lord to His murderers, but it did not secure their salvation or open to them the gates of Paradise. But if the murderers were to be signally favoured, from the pure benevolence and charity of the Saviour of the world towards them, because it behoved Him always to show Himself a Saviour, and He could never show Himself more completely such than by applying the fruit of His copious redemption to them in the very act of His Crucifixion, it was fitting that the one faithful voice which had been lifted up in vindication of His innocence and in confession of His dignity, should have a still more splendid recompense than that which was bestowed on His murderers, that the gift for him should be greater than the mercy to them, as his service had been rendered when it could so little have been expected, and with the risk of bringing down on the courageous soul who made the protest some aggravation of his torments, or at least the reproaches and reviling's of the world. We are here in the realm of immense and most magnificent bounties and mercies, and the whole character of our Lord's demeanour is so far changed. He is no longer silent and patient and meek in the hands of His enemies, like a criminal who feels that he is suffering what he has brought on himself. He speaks and acts like a Conqueror and a Sovereign, Who has made His triumph certain and can allot the fruits of His victory at His pleasure, to those who have deserved well of Him, or put Him under some obligation which is recognized by His most grateful Heart. Thus these two first Words prepare us gradually for the third.

Before we leave them, we may note one thing more which characterizes them, and which will help us to fix with greater certainty the meaning of the Word which is to follow. The boons granted or asked for the thief and for the executioners of our Lord, are applications of the merits of the Passion which was now being accomplished. The pardon asked for the enemies was a fruit of the Passion. The reward promised to the penitent thief was also a fruit of the Passion. The accomplishment of the great Sacrifice of Himself unlocked, so to say, the treasures of the mercies of our Lord, and gave" Him the right as well as the inclination to empty His love upon those who were now the objects of His special pity or gratitude. With this thought in our minds we may go on to the consideration of the third Word from the Cross, which is that which above all others has a special interest for us in the present inquiry.

"Now there stood by the Cross of Jesus His Mother, and His Mother's sister, Mary of Cleophas, and Mary Magdalene. When Jesus therefore saw His Mother and the disciple standing whom He loved, He saith to His Mother, Woman, behold thy Son ! After that He saith to the disciple, Behold thy Mother! And from that hour the disciple took her to his own." The meanings hidden in these simple words are capable of very long exposition, but we must be content with drawing out some of the most obvious and most important to ourselves. In the first place we must remember what has already been said, that the words before us, like the others spoken at the same time, must be under stood in the fullest and loftiest sense which can be given to them, and that we are now listening to the words of the Saviour from the Cross distributing, so to say, the fruits of the great triumph which He was now accomplishing. The first obvious meaning of the Word before us, which has been adopted by many of the Fathers, is that which has reference to the state of bereavement and loneliness in which the Blessed Mother would be left by the Death of our Lord. These Fathers see in the word a moral lesson, as St. Augustine says, by which children have the example of our Lord given them as to providing for their parents before leaving them in destitution. Our Blessed Lady was about to be left, not only, as she already was, a widow, but also a widow deprived of the companionship and support of her only Son, on Whom she depended for every thing that she could require. It was meet therefore that her Son should give her some one to take His own place towards her, as the support and consolation of her declining years. This our Lord did by looking on her and St. John at the foot of His Cross, and by commending her to him and him to her. And this seems to be confirmed by the words which follow, in which it is said, that from that hour the disciple took her to his own. When he took her to his own it must have been in obedience to our Lord's last injunction, and in acceptance of the trust or office committed to him thereby, and thus the action of the Apostle is a sufficient commentary to us on the words of our Lord, and explains the meaning which St. John attached to them.

But this interpretation requires deepening and intensifying before it can be admitted as exhausting the meaning of these great words. For it might be so understood as to signify something that might have been arranged as well at any other time as on this great occasion of the speaking from the Cross, something that would not rise to any very sublime commission or charge, something that would have little to do with the accomplishment of the great Sacrifice by means of which the Redemption of the world was brought about, something that would not be an application of its fruits and merits, something that might have been won by Mary at a less cost than the martyrdom which she had been enduring with so heroic a faith and constancy and fortitude, something which might have given her some consolation, perhaps, and have been accepted by her with her usual loving gratitude, but which would have been a boon comparatively poor for her at the time that her Son was disposing so royally of the fruits of His victory on the Cross. And thus we find that this interpretation does not altogether satisfy the Christian instinct about our Blessed Lady. The Son Who was speaking to her was more than the prop of her age and the comfort of her solitude in temporal matters. Her mothership was something more than dependence on Him in these respects But the words imply that John was to be to her, as far as might be, as our Lord had been and was and that she was to be to John all she had been and was to our Lord. And whatever the boon or the commission was, now conferred on our Lady and St. John, it must be something that was an application of the fruits of the Divine Sacrifice which was now being consummated, something belonging to the Kingdom which issued from the Cross.

It is clear that our Lord, in here addressing His Mother by the same name which He seems ordinarily to have used to her, may well be considered as having referred to the name which she tore in prophecy as the Woman promised from the beginning to our first parents, between whom and the serpent enmities were to be set by the hand of God, the Woman whose Seed was to be the Redeemer of mankind, the Woman who by a marvellous privilege was to "compass a Man," 3 that is to conceive a Man, the Messias Himself, in her virgin womb by the operation of the Holy Ghost. When He had used the word to her at the marriage-feast of Cana, it could not be said, as it is beautifully said about the present occasion by some of the Fathers, that He forbore to call her Mother, in order that the tenderness of the word might not increase her grief. It is well known that the rightful translation of the Greek word would probably be "Lady." But in any case it seems better, when we are dealing with this most solemn and awful occasion of the words on the Cross, to consider that the name was used with reference to the Scriptural position of the Mother of the Redeemer. This at once takes our thoughts away from the common consideration of our Lady as if she were only addressed as the mother of the young man raised from the dead at Nairn might have been addressed. The words were the words of the Redeemer, speaking to the appointed Mother who had been with Himself the subject of so much prophecy and anticipation.

When we put this thought by the side of the other, which has to be remembered here, that the occasion is that of the distribution of the highest crowns and recompenses of the Kingdom of redemption, we see no difficulty at all in understanding how our Lord is now committing our Lady and St. John the one to the other in place of Himself, making Mary the Mother of St. John in His own place, and St. John the son of Mary in His own place. And we see great reason for not limiting the relationship thus divinely ordained between them, to the attendance and care of our Lady, in temporal things, and the necessities of daily life, on the part of the Apostle, or to the motherly interest and loving dependence on her new Son on the part of the Mother, to which in other cases the words might seem to be confined. Such a limitation has never satisfied ordinary Christian devotion, although it is very true indeed that the example which the word would then contain, is beautiful and full of instruction to us. But we are led to think that it is more beautiful and more instructive than it would have been, if spoken by another person and of another person. We have to remember Who our Lord is, and who Mary is.

We have been engaged in tracing the position occupied by our Blessed Lady with regard to the work which our Lord came into the world to do, the work of the redemption of mankind, the founding of the new Kingdom of Heaven, with all the variety of its organization, through the whole of which is to run the strong mutual bond of the most tender, perfect, and Divine charity. In the earlier part of our Lady's companionship with our Lord she had had a share of her own in all the mysteries which succeeded one to the other, in the development of the Divine counsel regarding Him. When the time came for Him to begin His active course of preaching and teaching, and of the formation of His Church, we have seen her by His side almost continually, and quite continually occupied in a work of her own in correspondence with that work of His, following it with the most attentive contemplation, honouring it and doing it homage with the most grateful adoration, and aiding in the application of its benefits to the souls of men by the most fervent intercession. She lived for her Son and in the work of her Son. But now, as far as was possible to any creature, she had had a part in the way of sympathy and consent and compassion, in the fullest sense of the word, in the great and stupendous work of His redemption, not quite in the same way in which she had borne a part of her own in the Incarnation itself, but still a part of her own, in accordance with the dispositions of Divine Providence, which had ordained that she should stand by the Cross, and that all through the Passion she should be most closely united to His sacrifice of Himself. The first consent of Mary at the Annunciation, if all its freedom and deliberateness, gave her a share in all the issues of the Incarnation which must not be forgotten, even when we are speaking of the Passion.

From the time of the Incarnation, the redemption of the world by our Lord had occupied her thoughts and her heart entirely and absolutely. Meanwhile she had been mounting ever higher and higher from the very beginning in the scale of her marvellous sanctity, which was at the first a sanctity altogether unparalleled, and which had increased daily more and more, until the last few hours of the Passion had witnessed an increase out of all proportion to the marvels which had been witnessed before, by reason of the intensity of the sufferings which she had endured, the perfection of her union with the Divine will in her own crucifixion as well as that of her Son, and also because the Passion was a time of meriting altogether unequalled in itself, apart even from the intensity of her sufferings and the perfection of her conformity. It was as if all the creative and maturing power of a whole spring and summer had been condensed into a single hour.

Our Lady now stood under the Cross to hear our Lord allot to her her crown and reward, as He had just allotted the crown due to him to the penitent thief. It must be something which would correspond to the office which she had been discharging, not only during the whole of her life with our Lord, but especially at this last stage of that life in which the Passion consisted. It must be something that would be an embodiment to her of the immense graces and victories of the Cross, something which would be a trophy of the conflict, a memorial of the victory, a fruit of the suffering and the merit, a fountain of perpetual joy and power and beneficence, flowing from the achievement of the redemption in which she had borne her part. When we understand what is involved in and required by these conditions in the reward of our Lady, we can trace out without much difficulty what is meant by the words which bestow her, in lieu of her Son, on the Beloved Disciple, and made him her son in lieu of our Lord.

The charge or commission begins with the committal of St. John to our Lady as her child. "Woman, behold thy Son." She was to regard him as now representing our Lord in the new Kingdom, which was founded on the Passion. Our Lord could not mean that He was Himself to pass from her heart, for that would have been indeed a sentence of death for that blessed soul. Our Lord knew, as she knew also, that the separation between them was but for a few hours, and that He would then again be by her side until the moment came for Him to rise to Heaven. Nor in the interval of the forty hours was she to be without her usual keen sense of His spiritual presence, or ignorant of the marvellous mysteries which were taking place in the world beyond the grave. St. John was to have his peculiar and most blessed office of being her companion and guard after our Lord's departure, as long as she survived, though our Lord was to be always present with her in a new way, no longer that of visible presence. What our Lord had been in the habit of doing in the way of temporal care for her, guidance of her steps, and the like, that St. John, the Beloved Disciple, was henceforth to be. Our Lord had supplied the place of St. Joseph as well as His own. In this sense she was to depend on St. John in the place of our Lord.

He had been consecrated priest at the Last Supper, and he was to discharge to her that blessed office of ministering to her the Blessed Sacrament and celebrating for her the Adorable Sacrifice, and they w r ere to be the inmates of the same home, as had been the case with our Lord and His Mother, as long as there was a home for them. In other respects St. John was committed to her as the object of her love and of her prayers, the centre of her interests and cares. Not St. John alone, for he was but one of the Apostolic company, and all the Apostles, and indeed all the faithful, were committed to her motherly care by these words from the Cross. St. John indeed was very dear to our Lord, and so he was especially chosen as the guardian and companion of the Virgin Mother. But as the child of Mary, St. John, however specially dear to her, for the same reason as to our Lord, was the representative of the whole Church, in whose behalf our Lady was now to exercise by the special command of our Lord all her love and all her power. Her office was to be a continuance of that which she had already been exercising for so long, for she saw in the Church the work for which her Son came on earth, the one thing in the world for which He lived and for which He was to die. Whether her office be called intercession or patronage, power or influence, matters little indeed. The effect of these words of our Lord to her, which, as has been said, were creative words, and wrought what they signified, was to make her the Mother of the Church and of all its children, with the same devotion and the same Divine grace for the discharge of her duty as had been hers in the discharge of her motherly duties to our Lord Himself.

One thing, however, was changed—that she was now the Mother of Him Who had accomplished the work of redemption, the work of which He had said, how was He straitened until it w>as accomplished. The fire which He came to send on earth was now not a thing of the future only, but it had been already kindled, the debt had been paid to the justice of the Eternal Father, the treasures of grace had been won, and were now to be administered and distributed. By the difference between our Lord's Kingdom in general before and after the Passion, we may measure the difference between the power of the prayer and patronage of Mary as they had been, and as they were henceforth to be.

We must not forget, as has been said, that the charge given by our Lord in this third Word from the Cross was not only to His Blessed Mother. It was also to St. John, first in his own person, but also as the representative of the whole Church. It might perhaps have, sufficed in rigour to make only one Word, in which either Mary might have been told to ''behold her Son," or John might have been told to " behold his Mother." The one charge might have been considered as including the other. But this was not what our Lord chose on this most solemn occasion. His Words were few indeed, but still He chose that in that small number both the separate charge to Mary and the separate charge to St. John should have a place. This shows us, at all events, the immensity of His love for this new relationship which He was creating, and His great desire that both parties thus bound together should fully understand their duties to each other, and the claims they had on each other. And St. John seems to take care that we should understand this, and that he immediately acted on the injunction of His Master, for he tells us of this second charge and of its effects on himself. "After that He saith to the disciple, Behold thy Mother. And from that hour the disciple took her to his own." The words cannot signify his own home. For it was not for some considerable time after this Word of our Lord that either Mary or John could have left Calvary, nor is it at all probable that St. John had a home of his own to which he could take this Blessed Mother. He had probably never had a home of his own, apart from the house of his parents in which he had been brought up, for he had never married.

The best translation of the Greek words is probably that with which we are familiar, "He took her unto his own." That is, he made her in every respect his Mother. The relation between mother and child is the tenderest that we have any experience of, and all the world understands it as such. The foundation is always the same, though the form in which the relationship works in practical life varies indefinitely with circumstances and times. When the child is an infant the mother is everything, and provides it with everything. When the mother is aged and feeble, the relationship is the same as ever, but it is now the part of the mother to be dependent and of the child to support and provide for her. So the circumstances of health or sickness, poverty or wealth, power, station, and the like, make number less alterations in the exercise of the duties and affections which the relationship implies. In the case of our Lord with His Mother, He was the most dutiful and reverent, as well as the most loving, of sons. But He was her God, and He came into the world as Man for a special work for His Father's glory, over which she could have no control. Thus His conduct to her, as we have seen, varied in certain details at various times. But He was always her Son and she was always His Mother, and as her Son He gave her the whole love of His Heart, as she gave Him her whole love as His Mother.

The relation between St. John and his new Mother, and between all those who were represented by St. John, when this commission was given to him by our Lord, must be measured in the same way. Or rather it can have no measure beyond what follows naturally from the position of the Mother and the children in the Kingdom of our Lord. St. John knew the dignity, the sanctity, the dearness of our Lady to our Lord. He knew her unique elevation, and the designs of God with regard to her. By the side of these the duties imposed upon him of her protection and guardianship, of attending to her few wants and giving her the comfort and consolation and companionship of a son, would seem to him light burthens indeed. The balance between what he could do for her and w r hat she could do for him would certainly not seem to be struck on her side. He at least was the gainer by the Divine Word which knit them together. He could give her the love of a heart that had caught some of our Lord's own intensity of affection by leaning on that Sacred Bosom, but he was to receive in return all the love, the tenderness, the watchful care, the powerful protection of the heart of that incomparable Mother. All her love for our Lord was to work itself out in love for him.

Moreover, St. John did not perhaps perfectly understand, at this time of the Passion, the whole of its effects, and especially the whole of its results with regard to the Blessed Mother, what was the counsel of God in setting her to suffer so much by the side of our Lord, what w r as the reward which would be proportioned by the decree of God to her faithfulness in this last and greatest trial, and to the intensity of her sufferings, and how what we call the communication of the Passion to her involved a very great power in the application of its fruits by her patronage and intercession. But he must soon have learnt these things after the Resurrection of our Lord, in the course of his subsequent intercourse with our Lady, and of the unfolding of the history of the Church, in which he himself was to have so large a part. What he would feel all through would be that, whatever Mary was in the Kingdom of her Son, she was to him principally and above all things his Mother, so instituted by the special act of our Lord dying on the Cross. Our Lord's thoughtful love had chosen this most solemn moment of His whole Life, when the great Sacrifice of the Cross was being accomplished, and the whole treasures of Heaven were laid open to Him for the children of men, to make this most sacred alliance between Mary and His Apostles. Whatever Mary had was his, as her son. Whatever that most loving and charitable and grateful heart could do for him or win for him, was his. She was in truth to live for him and he to live for her, in the same way as she had lived for our Lord and He for her. She might rise ever higher still in sanctity, even after the Ascension and the Day of Pentecost, she might pass out of this world to her throne on high, and he might see her no more on earth. But ever and everywhere she would be his Mother. The relation had been made by God, and no one could put them asunder. The ever increasing height of her elevation could not raise her too high for this relation. It only gave her greater opportunities of love and beneficence, as her power and her charity increased, in proportion as she drew ever nearer and nearer to God.

This relation between Mary and the blessed Evangelist and Apostle is an instance of a class of truths or facts in the Kingdom of our Lord, the best explanation and commentary on which is to be found in the spirit, the mind, the heart, and the practice of the Church. We live at the end of so many centuries after the Crucifixion, and we may fairly look around us and ask ourselves, What is the fruit of this great Word of our Lord from the Cross, how is it understood in the Church, and what results has it produced ? And the answer that springs to our lips is, The result and fruit of this Word of our Lord are to be found in the whole history of the devotion of the Church to Mary, and of the marvellous benefits which have resulted from that devotion. For the heart of the Church has never allowed of the thought that this was a personal gift to the blessed Apostle, which was confined to him, and ended with him. She might as well have supposed that when our Lord gave St. Peter the Keys of the Kingdom, or when He promised to be with the Apostles all days unto the consummation of the world, those gifts came to an end when the persons to whom the words were spoken passed from this earthly scene into another world. There are reason able arguments enough which, in this case, would make such an interpretation impossible, for how can it be thought that St. John would have put on record a merely personal boon to himself ? But if such reasons did not exist, still the instinct of the Church would have been from the first that such could not have been the thought of the Sacred Heart, such could not have been a gift to satisfy the heart of Mary.

It has been said elsewhere that it may be thought probable that, if we had more records and more information to guide us positively as to the manner of regarding the Blessed Mother of God which was ordinary among the Apostolical Christians, we should not find that there was any great difference between ourselves and them, in this particular. 4 But even if this conjecture were not true, we should still be quite safe in finding an answer to our question about the results of this Word, in what we know of the mind and habits of the Church all over the world, for so many centuries subsequent to the Apostles. If it were not so engrained as it is in the mind of the Christian people, that Mary is a Queen in the Kingdom of her Son, and that she is our Mother, so made by the special appointment of our Lord, which includes an injunction on us of honouring her and having the most trustful recourse to her as such—if the whole world were not full of the memorials of her constant care for the Christian commonwealth— if the calendar were not full of her feasts, if the private devotions of Christian families were not so constantly placing them at her feet, if the saints of God whom the Church sets up as our models of love of Him were not so uniformly conspicuous for their love of and trust in her—if, in short, Heaven and earth were not full of voices telling us how good a Mother we have in Mary, perhaps we should not venture to say so certainly that this Word means what we believe it to mean. For then we should have to account for the want of correspondence to so plain an injunction on the part of those who have gone before us in the Church. There would be evidence one way, instead of the other. But as the facts of history are what they are, they furnish the best of explanation of the text of which we are speaking. They show us that it was not a passing word of kindness and affection, but an occasion on which the foundation was laid by Divine and creative words, for one of the greatest of the earthly glories of God and blessings to mankind. They show that the Church has caught up what our Lord said and did, with an instinct which comes from the union of her heart with His, and has taken care that these Divine words shall not pass away.

After the third Word, addressed to His Mother and to St. John, our Lord may be said to have spoken no more directly to any human being. The four last Words were either addressed to God and His Father, as the fourth and the seventh, or they were ejaculations, one of which, the fifth Word, was no doubt spoken for the purpose of producing some action on the part of those who heard Him, that is, the giving Him the sponge full of vinegar. The fourth Word, then, was the verse from the beginning of the twenty-first Psalm, which He uttered in Hebrew, "Eli, Eli, lamma sabacthani, My God, My God, why hast Thou forsaken Me ? " and the seventh Word, " Father, into Thy hands I commend My Spirit," is found in the thirtieth Psalm. Some devout persons have supposed that our Lord recited to Himself all the intermediate verses be tween those two which He uttered aloud. If this could be ascertained, we should have a long subject for meditation in the hundred and fifty verses which intervene between the first of these verses and the last.

There seems also good reason for thinking that all these four Words were spoken quite at the end, or nearly at the end, of the three hours. For St. John tells us that the fifth Word, "I thirst," was spoken in order that the Scripture might be fulfilled, that is, in order that what he relates might take place, that the vinegar might be given Him, as has been said, and that thus this last particular of the prophetic description of the Passion might be supplied. The sixth Word, "It is consummated," naturally followed immediately on the accomplishment of the Scripture, and the final Word, "Father, into Thy hands I commend My Spirit," would come directly after that. There remains only the fourth Word therefore, in which, because He spoke in Hebrew, some of the bystanders thought that He was calling on Elias. As to this, it may not seem so certain that the time can be fixed. Still, this Word is apparently connected, in the narrative of St. Matthew and St. Mark, with the exclamation of thirst. For these Evangelists tell us that it was after the fourth Word — they do not mention the fifth—that the sponge full of vinegar was offered to Him, and that then it was said by some one there, " Stay, let us see whether Elias will come to deliver Him/' There must therefore, it would seem, have been no great distance of time between the fourth Word and the fifth, which last is mentioned by St. John alone. There would there fore seem to have been a long period of silence, for the two first Words must have been spoken early in the three hours. We cannot tell at what time precisely the third Word was uttered.

These four last Words need not be commented -on by us at any great length. They must have sunk into the tender heart of our Blessed Lady with immense pain, for they showed how terrible still were the sufferings of our Lord, notwithstanding the utter exhaustion to which He was reduced, which might have taken the place of positive pain. The first of these words revealed the absolute dereliction and desolation of His Soul. His Soul was always united to the Divine Person of the Word, and in this respect it could never .be abandoned or forsaken. Even after the separation between the Soul and Body of our Lord, the Divinity remained united to each. Nor again could there be abandonment of one of the Divine Persons by the other two, nor could our Lord's Soul lose the Beatific Vision. Nor could the Soul of our Lord be abandoned by God, in the sense in which the sinner is forsaken by God when he commits a deliberate and grave sin. But our Lord suffered in His Soul the extreme of dereliction which was possible to Him, in the utter destitution in which He was left of all consolation, comfort, spiritual joy, and the like, and this, which He chose to undergo for our sakes, was an immense torment, and one which He chose that we should know that He had suffered, in order that when we are exposed, as may sometimes be the case, to far less torments of the same character, w r e might be able to take refuge in the thought of His Passion, which included this dereliction. And to our Blessed Lady, who knew so w r ell the whole range of the ineffable consolations which come from the sensible presence of God in the soul, it must have seemed an unutterable pang that her Son should suffer in this way also. It might have seemed that the chalice of the Passion had nothing more left in it for Him to quaff, and now there was this piteous cry from Him Who never complained, which revealed the truth that He allowed Himself to approach the very lowest depths of possible miseries. For the dereliction of the soul by God, in the fullest sense, in which it could not be in Him, is the very last extreme of the sufferings of the lost. It has been thought that our Lord may now have had before His mind that most utter disappointment, of which mention has been made in speaking of the Agony in the Garden. This consisted in the clear foresight that there were to be so many for whom all His labours and sufferings would be in vain, or still more, the occasion of the aggravation of their sins and so of their punishments hereafter. This thought may have accompanied the extreme withdrawal of all consolation of which mention has been made. But to our Lady it would not be so much the cause of the suffering of our Lord at this point which would be so painful, as the knowledge of the suffering itself, and that our Lord thought so much of it as to vent His grief in the plaintive words of the prophetic Psalm, in which so many of the details of the Passion are set forth.

The fifth Word may have been a simple expression of the fact that our Lord allowed Himself to suffer that most intense anguish which is caused in the dying under certain circumstances by the extreme thirst to which they are subjected. For this is a pain of which numbers have experience who do not die by any violent death, and thus it may have been a compassionate condescension of His, that we might know that He had undergone it and sanctified it for us. Others have seen here the expiation for that terrible sin of drunkenness, which does so much to desolate the world, and hence there has sprung up a reparatory devotion to the Holy Thirst. In this sense it seems natural enough to understand the words in their simplest meaning, and our Lord is said by the Evangelist who relates them to have spoken in order that the Scripture might be fulfilled. But of course we cannot forget the other and far more excruciating thirst, that of the Heart of our Lord for the conversion of sinners and the salvation of men, in His burning suffering from which He is but too often treated in the same way as now in His Passion, by having His thirst met by what can only aggravate it and add a kind of insult to the cruelty with which His complaints are returned. And our Blessed Lady could well understand all the torments which He had to endure in that last hour of terrible thirst, for He had no relief or food since He left the Cenacle the night before, and almost the whole of the intermediate hours had been crowded with exertions and sufferings of various kinds. Besides this, His loss of blood had been enormous, amounting almost to the total emptying of His veins, and this of itself is enough to bring on the most torturing thirst. And still more would she enter into the thirst of the Sacred Heart of which we have spoken. Moreover, we must remember the peculiar pain which she must have felt in seeing herself there close to the side of her Son in His bitter thirst, and without the power to alleviate His agony by so much as a cup of cold water. She must leave the satisfaction of His need to His enemies, and witness the aggravation of His pains by the offering to Him of the sponge full of vinegar.

When we arrive at the sixth Word, we seem to be drawing near to the moment of victory and triumph. For there cannot but be a satisfaction in the thought that any great work has been accomplished, and an immense boon for the whole world won. And yet, regarding these words from the point of view of the Blessed Mother, there was a terrible pang in store for her, the approach of which she felt more and more nearly, as the swift minutes ebbed away which w r ere yet to intervene before the fulfilment of the three hours. It was a note almost of triumph for our Lord that He could say that all was consummated, the satisfaction for sin, the restoration of the glory of the Father, the salvation of mankind, the foundation of the Church, the opening of the Kingdom of Heaven, and that all the pains and humiliations of the Passion were soon to be over, and the great struggle for the overthrow of the kingdom of Satan perfectly completed. All these things would be joy to the heart of our Blessed Lady also, for she loved nothing but the glory of God and the success of the work of her Son, nor could she fail to rejoice over the defeat of Satan, nor could she wish the Passion itself to be prolonged. But when the Passion should be accomplished finally, there must come death—the separation of the Body and Soul of our Lord, the cessation of that blessed life of the Sacred Humanity, and she would be left, and the world would be left, without Jesus Christ! This was the prospect included in the announcement of the consummation of the great act of God's justice of which she had been for many hours the witness, writing in her heart of hearts every pang, every insult, every word and action of her Blessed Son. No doubt as, all through, she had looked first of all to the will of God and His glory in the execution of the Passion, so now the thought that the victory was accomplished, and, as Daniel says, ''eternal justice brought in" by the work of her Son, would be uppermost in her mind. But in her, as in our Lord, there was no confusion of one thing with another, no overlaying of pain by joy, no smothering of anguish in oblivion on account of some countervailing affection. Her heart had to prepare itself for the sight of His breathing out His last, and this was nearer and nearer to her with every one of the words that fell in succession from His lips. And the same may be said of the last great cry, when our Lord most lovingly commended His Soul to His Father. It was a moment full of the holiest affections—a sacramental moment, we may say, for it was the consecration of death for all mankind by the touch of the Incarnate God. It was the turning the enemy who had been let loose on man by the sin of Adam into a friend, and whose hands were full of graces and gifts. But still to the heart of the Mother at the foot of the Cross it was, with all its elements of triumph and consolation, a moment of the deepest pang that human heart can feel, in the destruction of the life in which she had lived more than in her own.

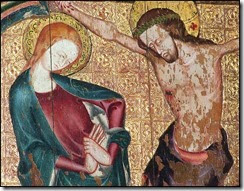

Thus we notice here what has already been remarked on, that the Compassion of our Lady lasts on much longer than the Passion of our Lord. The moment of His death changes the whole tenour of His existence, for He at once enters on a world far nobler than this, the world of the departed spirits, and in this He is at once acknowledged as King and Deliverer, His enemies falling back and fleeing before His Face, His saints flocking forth to meet Him at the gates which had been broken down by the breath of His approach. His Soul is in glory and beatitude, and He finds Himself at once the source of untold joy and unmixed blessings to thousands and thou sands of His redeemed. But we must not endeavour to follow Him at once over the new realm on which He had now entered as Sovereign. Our place must still be on the mount of shame and suffering, where the lifeless Body hangs on the Cross, and the Mother and St. John and Magdalene are still watching as the darkness rolls away, and the daylight returns for the space between the ninth hour and the setting of the sun. There is silence there. Only the centurion makes his confession of faith, and the crowds retire beating their breasts. Even the great portents, the rending of the veil of the Holy of Holies in the Temple, the earthquake, the opening of the rocks, the appearances of the saints, what were they all to those who stood gazing on the Body in which life had been and in which life was not ? But now Mary's part is to begin. In the depth of her grief she has to act and to direct others, while, as far as human powers go, she is as helpless as was ever the mother of one who had been executed on a cross.

But Mary could not feel helpless, it was now that she showed even more than before, the immense fortitude and calm wisdom which were but natural accompaniments to her glorious faith and intelligence of the ways and counsels of God, her part was to pray without anxiety amid all her grief. She knew that God would not leave her without help in her office of seeing to the last honourable services which were due to the Sacred Body which hung there on the Cross. It must be taken down and prepared for burial, a grave must be found, and It must be deposited there with all the reverence and worship with which the Church adores the Blessed Sacrament when reposing in the sepulchres in the churches between Holy Thursday and Good Friday. Even in the deepest human grief it is a relief to have something on which to occupy our minds and cares in the way of service to the de parted, and with our Blessed Lady there was no pause for the simple indulgence of grief. She was helpless to the outward eye, but she was mighty in the power of her irresistible prayer.

It must have been before the Death of our Lord and the portents in the temple and in the city by which that Death was accompanied, or immediately followed, that the Chief Priests, in their thoughtfulness for everything that might tend to the dis honour of our Lord, begged Pilate that he would give orders that the legs of the crucified persons might be broken so as to accelerate their death, in order that the bodies might be removed from the sight of men before the evening came which ushered in the approaching Sabbath. Orders were accordingly given, and the first incident on Calvary after the expiration of our Lord and the departure of the people beating their breasts, was the appearance of the party of soldiers charged with the execution of these orders. The Evangelist who witnessed all that passed, tells us that they came, and finding the two thieves still alive broke their legs, as it seems with massive iron rods or hammers, but that when they came to our Lord, they saw that He was dead and did not therefore break His legs. The Sacred Body was thus spared the insult and profanation which would have been involved in this, and the soldiers unconsciously fulfilled the Scriptural precept about the Paschal Lamb, that "not a bone of it should be broken." 5 Thus one great danger and anxiety was over. But immediately there followed what seemed like a wanton insult on the part of one of the soldiers. He ran at the Body of our Lord with his lance, and pierced it with a deep wound on one side of the Heart, passing his spear through the Heart itself, and making the point appear on the other side. This poor soldier may have been actuated by a wish to make the Death of our Lord beyond all question, and in this he may have acted under the same Divine guidance which shows itself in many of the incidents of the Passion and the Resurrection, providing the most irresistible arguments for the perfection of the proof of our Lord's Sacrifice and Resurrection from the dead. For, merely as a contribution to the evidence of our Lord's Death, this act of Longinus was most wonderfully appropriate, for it could never be said after this that there had been any mistake, that the other two crucified with Him had been found alive by the soldiers, and that it was highly probable that their impression of the Death of our Lord was erroneous.

But God had higher designs than this in the action of Longinus. We are certain of this from the solemn manner in which St. John speaks of it in his Gospel. " But when they came to Jesus, and saw that He was dead, they did not break His legs, but one of the soldiers opened His side with a spear, and immediately there came out Blood and Water. And he that saw it gave testimony and his testimony is true, and he knoweth that he saith true that you also may believe. For these things were done that the Scripture might be fulfilled, * You shall not break a bone of Him,' and again another Scripture saith, 'They shall look on Him Whom they pierced.' 6 The fulfilment of the Scripture in this, as in the other case of the not breaking His legs, is an addition to the complete argument from the correspondence between the prophetic description of the Passion and its actual history. But the language of St. John, in speaking of the opening of the side of our Lord, seems to signify that there was something more included in this action. Here again we have the universal feeling and sense of the Church to guide us in our commentary on the words of the Evangelist. The Fathers tell us that in this incident we have the representation of the birth of the Church from the side of our Lord, a birth which had been foreshadowed in the creation of Eve, who was taken by God from the side of Adam while he lay in a deep sleep. Our Lord indeed lay in a deep sleep, for it was the sleep of death, when His Spouse \vas born from His side. And this commentary may be said to rest on the authority of St. Paul, who, in his famous passage about the union between man and wife as representing that between Christ and the Church, refers distinctly to the words of Adam about Eve, saying, "We are members of His Body, of His Flesh and of His Bones," and then he goes on to quote the very words which follow, "For this cause shall a man leave his father and mother, and shall stick to his wife, and they shall be two in one flesh." It is clear that the Apostle had this mystery of the piercing of the side in his mind when he wrote that passage. 7

The Fathers tell us that the Blood and Water which now issued from the pierced Heart of our Lord signify to us the Church, because the Church is formed from the two great Sacraments of Baptism and the Holy Eucharist, represented, the one by the Water, and the other by the Blood which issued from the open side of our Lord. Thus Mary was present on this occasion of the birth of the Church, and although the Evangelist may not at the time have understood the mystery, it is natural to sup pose that our Blessed Lady was not without an intelligence of what was taking place. Tradition goes on to say that she was praying for Longinus, who was inflicting so sore a wound on her own heart by his rude cruelty to the Sacred Body, when some of the Water which came forth from the opened side would strike on his face, and produce a miraculous cure of the weakness of eyesight under which he laboured. This Water is considered, moreover, to have acted as the Water of Baptism for him, and he was then and there illustrated a marvellous interior light, which enabled him to see the dignity and office of Him Whom he was thus insulting, and brought about his conversion.

Thus once more the good Providence of God had watched over the bereaved Mother in her loneliness on Mount Calvary. But there was as yet nothing visible in the way of help for the great undertaking of the deposition from the Cross and the burial of our Lord. The time was drawing on, and soon the evening would be falling. Mary's prayer continued, and before long its fruits were seen. Indeed, its power had already been working. While the scene of the piercing of the side was passing on the hill of execution, the Providence of God was bringing about, in its own way, the burial of our Lord. There were in Jerusalem probably more than the two men whose names have been preserved to us, Joseph of Arimathea, and Nicodemus, who were secretly disciples of our Lord among the higher classes in society, men who longed for the salvation of Israel, but who were for the time too timid to venture to declare them selves, in the face of the certain opposition and persecution to which they would be exposed from the priests in power. They had not been bold enough to make any open resistance to the violent and savage measures of the dominant party, though they had refrained from all open participation in the steps taken for the condemnation of our Lord.

It might be natural that the scenes of the day which was now drawing to its close, should have sufficed to drive them still more into retirement and concealment, and have taken away what little courage may have remained in them for any avowal of their reverence for our Lord. But the grace of the Passion was working in their hearts, the grace which had made the thief on the cross bold enough for his confession of faith, the grace which had converted the Centurion who had been in charge on Mount Calvary. These were just the men who were needed for the occasion of the sepulchre of our Lord. Their rank and wealth and position gave them free access to the Roman Governor, who would be ready enough to oblige them, especially in anything that might seem to favour the honour of the Crucified, for Whom he himself had felt so much sympathy. Thus a bold and determined act on their part would meet with no opposition, although it might lead afterwards to consequences which might involve suffering to them. It is not certain that these two acted in concert at the beginning. Joseph went in boldly, the Evangelist says, to Pilate, and asked for the Body of Jesus. Pilate was not certain whether He was already dead, for it may have been almost at once after the order had been given for the breaking of the legs that Joseph made his request. The Centurion set him at rest on this point, and Pilate gave Joseph leave to do as he wished. As he seems to have come to Calvary in company with Nicodemus, who had also prepared a large quantity of spices for the embalming of the Sacred Body, it is likely that he had communicated with him as soon as Pilate had given his permission. Joseph had brought the sheet in which the Body was to be wrapped, and the two with some of the servants now made their way to Calvary.

Thus came about that most touching scene of the deposition and burial of our Lord, according to the desires of the Heart of the bereaved Mother, who never left Him till He was placed in the tomb. The tomb was close at hand. It had been prepared by Joseph for his own burial. But now he made it over to our Lord, and it was to become for all ages the holiest spot on earth, though its history is a sad comment on the treatment of our Lord and His religion on the part of the world. The two noble servants of our Lord paid due honour and homage to our Lady on their arrival on Calvary, and then, with her consent, proceeded to their holy work. Maria de Agreda has described the whole in a few graphic sentences. Our Lady, we are told by her, was asked, first through St. John, and then by Joseph himself, to withdraw to a little distance, but she refused, saying she had seen our Lord crucified, and could not shrink from seeing Him taken down from the Cross. The utmost reverence was observed, as if they had been priests ministering at the altar. The Crown of Thorns was gently and reverently detached from the sacred brow, and given to our Lady, who at once knelt to it, and gave it its due honour as a most holy relic. The nails were taken out with infinite care, and given in the same way to our Lady. That was the beginning in the Christian Church of the veneration of the relics of the Passion.

Next there came the more difficult task of lowering the Sacred Body itself, gently, slowly, carefully, that there might be no slip or sudden fall or shock of any kind, till at length, after the most reverent handling on the part of the two men and St. John, it was laid in the arms of the Mother who had first embraced it in the stable of Bethlehem. All due worship was rendered to it both by Mary and the saints assembled with her, and thus it rested for a time, amid the adoring sobs and tears of the whole company, until the remembrance of the approach of evening roused them up to proceed with their mournful work. The handling of the Sacred Body was now left to the Blessed Mother. She it was who arranged the limbs and the hair, wiping away too, as far as could be, the traces of the cruel treatment to which it had been exposed, but leaving the precious drops of Blood, and closing up the gashes and wounds with the precious herbs and unguents which Nicodemus had brought. All was done swiftly but not hurriedly, in the quiet composed solemn manner in which all the actions of our Lord and His Blessed Mother were performed. Magdalene was there, at the Feet, St. John at the Sacred Head, and she at least was not satisfied in her devotion, for she would have come on the third morning after to finish the work of embalming. After a loving adoration, the Sacred Body was enfolded by Mary's own hands in the sheet which was to become one of the most precious relics of the Church, and then, with thousands of angels invisibly accompanying them, the holy band of disciples and faithful women, swollen now, per haps, by some few who had come from the city, formed the funeral procession which was to bear our Lord to His last home. St. John, Joseph, and Nicodemus were joined, we are told, by the converted centurion, and bore the Sacred Body. Our Lady followed with Magdalene, the Maries, and the other women and disciples. The sepulchre was but a few steps from Calvary. So wonderfully had everything been arranged for the convenience of the burial. One last act of adoration, one last look at the holy Face, and then the stone was rolled to the door of the sepulchre by Joseph himself. Mary rose from her knees to depart, with St. John, but it seems from the Gospel account that the tomb was not left altogether and at once. The tender devotion of Magdalene must have its fill. "And there was Mary Magdalene, and the other Mary, sitting over against the sepulchre." The Roman guard would soon be there, and their presence would drive away the holy women.

It was probably our Blessed Lady's perfect calm and self-command that made her set the example to the others of leaving the sepulchre. It would have been natural for her to be the last, but she was not. She had work to do for our Lord, which the others had not to do. She was the centre now of the scattered flock of her Son. She adored the Cross on Calvary where it was left standing, and then went her way, as it seems, to the Cenacle, which was at no great distance. Her heart was with our Lord. He was actively occupied at this time, and ever since His Soul had left His Body, in the work of consoling and blessing and crowding the holy souls, who had waited so long for His arrival in the abode of the departed. Probably, could we trace out the tale of His activity in the forty hours which He spent in the realms below, we should see that never in His earthly life had He done so much and so many things for the glory of His Father and the good of men. Our Lady was to spend Holy Saturday, not indeed in activity like His, but in work which it was her part to do, and which was the holiest work on which any one left in this world could be employed.

1 St. Luke xxiii. 34.

2 St. John xv. 24.

3 Jerem. xxxi. 22.

4 See The Preparation of the Incarnation, Note to Ch. iii.

5 Exodus xii. 46.

6 Zach. xii. 10.

7 Ephes. v. 30, 31 ; Genesis ii. 23, 24.